Black Market Lotteries In The U.S.: When The Policy Game Ruled The Day

Lottery Geeks explores the world of black market lotteries and why they have become extinct in the modern-day gambling scene.

3 min

State-sanctioned and state-run lotteries are so plentiful these days that it’s hard to imagine a time when they were not en vogue. But it doesn’t require flipping too far back into the history books to find a time when lotteries were frowned upon or considered taboo.

Such a notion did not stop the demand for the vice.

Organized crime groups filled the void by offering something called “The Numbers Game” or, in some circles, “Policy Game.” There were also other names for the games, names that varied from location to location.

Here, Lottery Geeks investigates black market lotteries and explores their significance in the evolution of the lottery.

Humble beginnings

In the 2010 book, Our Police Protectors: History of New York Police, it’s noted that as far back as the 1860s, one could go to downtown Manhattan and find what the author describes as “policy shops.”

In those illegal establishments, visitors could partake in the vices of the day. Some shops would offer the ability to play casino games like blackjack and roulette, while others dabbled in the “Policy Game.”

Much like a modern-day lottery, players could select between numbers 1 through 75. The numbers would be serialized and drawn. If someone picked the right combinations, that person could win the game.

The buy-ins were relatively cheap, even taking into account inflation: one cent per play or ticket, and some bookmakers accepted credit bets. These games often targeted people of lower socioeconomic standing, including African Americans and Italian Americans. Cuban Americans and Puerto Ricans also played the game but called it “bolita,” which roughly translates to “little ball.”

Evolving the game

In the 1890s, a gentleman by the name of Samuel Young, who later became known as “Policy Sam,” would introduce the black market lottery game in Chicago. It was basically the same offering as in New York, but Policy Sam focused particularly on marketing the game toward African Americans.

Nate Thompson’s book Kings: The True Story of Chicago’s Policy Kings and Numbers Racketeers, An Informal History, actually says the game dates back to the 1840s in Chicago. The book claims that Young was growing the game, not necessarily introducing it in the city. Indeed, there are different versions of the story depending on who tells it.

Either way, the game grew to be played by a large audience, and managed to steer clear of law enforcement’s watch for the most part. Throughout Lottery Geeks‘ research, mentions were made that most cops, especially in New York and Chicago, were paid to look the other way.

From there, several organized crime syndicates would set up their own policy games, and the concept would spread to different parts of the U.S. The game expanded in a big way during the start of the 20th century.

An interesting twist on the game

In Boston, the game play differed slightly. Customers would buy a ticket in the same way and pick their numbers, but the way in which winners were chosen was completely different.

Instead of drawing a ball, the winning numbers came from the digits in the betting handle of the early races at Suffolk Downs. On the days when Suffolk Downs was not running, the numbers would be “drawn” from a New York track.

According to a source Lottery Geeks spoke with who wished to remain anonymous, there were instances where “the handles would be manipulated by rival syndicates” to hurt their opponents’ number games operations. In other words, horse races were fixed.

A good (though fictional) example can be found in the television series Godfather of Harlem, where one of “Bumpy” Johnson’s rivals manipulates the outcome of a race so that Johnson has to pay out a large grand prize, a sum that his operation cannot cover. The move ruins Johnson’s ability to run not only his smaller policy game operation but also his other businesses.

Although this was a written-for-TV scenario, multiple sources indicated such things happened in real life whenever two or more syndicates were “at war.” Wars are common in the criminal world, but the anonymous source with knowledge of organized crime processes indicated that there was an uptick in race fixing prior to Prohibition.

A reckoning For black market lotteries

Law enforcement was generally not fond of policy shops. These shops helped organized crime to thrive throughout the United States. In the early 1940s, efforts were made to remove these operations in areas like Detroit by rounding up the people responsible for running them and putting them on trial.

Eventually, organized crime syndicates found ways to open new shops, but they did it very quietly. That is when the phenomenon of having people “run numbers” really picked up steam. Instead of having a central location, someone would run point, collecting tickets from players, deliver them to the syndicate, draw the numbers, and pay the prize to the winner. This method of doing business was lower profile and harder for law enforcement to catch.

According to Scott M. Bernstein, an organized crime historian, these operations actually influenced a lot of states to open up their own regulated lotteries, to take the power from the racketeers while ensuring that the state gets to benefit from the profits of the lottery. If the states could not stop organized crime from running the game, they wanted to give players one they would prefer to play due to added incentives.

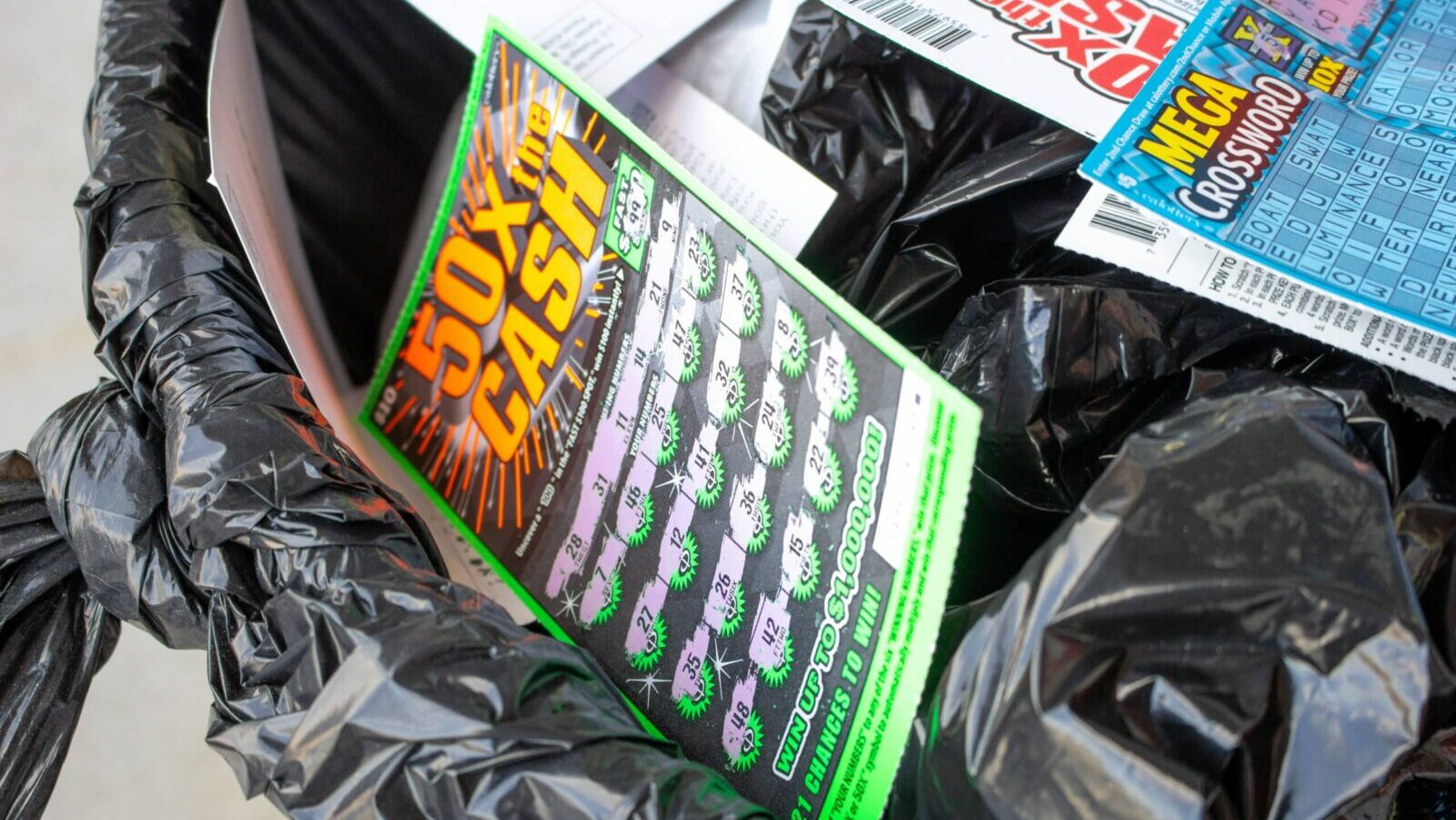

Certain states, like Massachusetts, opening their own lotteries in the mid-to-late 20th century snuffed out that revenue stream for organized crime syndicates in the area. Of course, the syndicates found new ways to make money, such as through sports betting. But the “numbers game” essentially vanished, even in states that still do not have a lottery today, like Alabama.

At least, that appears to be the case, based on Lottery Geeks’ reporting. For all we know, there may still be underground shops running small-scale, black market lotteries and getting away with it.