Full Of Hope: Lottery Scholarship Dollars Have Reshaped The College Landscape In Georgia

Georgia is the rare state where all lottery proceeds are channeled toward schooling — primarily in the form of the HOPE college scholarship.

4 min

Thanks to fellow Georgians’ eagerness to play a state-operated game of risk, Jordan Madden attends a reputable university free of charge.

Without it, Madden figures he would be enrolled at a community college or a more affordable, lower-level school. Instead, he stands one year away from a degree in public policy at Georgia State in Atlanta.

Picking up the tab for him and scores of other in-state students are purchasers of tickets sold by the Georgia Lottery. It is the rare state where all lottery proceeds are channeled toward schooling — primarily in the form of the HOPE college scholarship for undergraduates, which is widely considered the nation’s gold standard for such aid.

“It really does a great job in helping students across the state to have access to higher education,” Madden said.

Especially himself. Having tuition paid for has freed Madden up to engage in campus activities and seek internships rather than holding down part-time jobs.

“HOPE helped me beat that [financial] burden,” he said. “I don’t have to worry about working as much.”

The merit-based Approach

Because the scholarship is awarded on merit with a minimum 3.0 grade-point average upon graduation from high school and throughout college — as opposed to most other states, which tie their lottery-funded aid to financial need — the influx of higher-achieving students has enhanced the reputation of Georgia universities.

The plan enables Georgia to retain some of its more academically accomplished pupils who can avoid shelling out for more expensive options across state borders. Applications have risen at the major schools, as have GPAs for those applicants, though a direct correlation has not been confirmed through known studies. Home-grown entrants have driven the hike in enrollment numbers.

Over the past five years, the number of degrees conferred by the state university system has climbed by nearly 11%, while the average high school GPA for first-time freshmen has jumped from 3.29 to 3.41.

“We do believe anecdotally the amount of money being invested in higher education in Georgia has made a significant impact,” said Lynne Riley, president of the Georgia Student Finance Commission. The lottery “has enticed the best and brightest to stay in Georgia for their education.”

A bonus, Riley added, is that a wide swath of graduates remain in-state to bolster the workforce there.

Millions of students, billions of dollars

Since the lottery’s launch in 1993, some 2.1 million students have received assistance through the program for what is expected to hit $15 billion this year.

The University System of Georgia, providing data dating to 2005, indicated that 70% of graduates with bachelor’s degrees have received the HOPE or the more restrictive Zell Miller scholarship — named for the governor whose administration initiated the lottery, which backs both scholarships. Some 54% of those graduated with no college debt.

The scholarships “clearly benefit Georgians and have helped create a more educated Georgia,” the University System declared in a statement.

Seventeen states are listed on the North American Association of State Provincial Lotteries (NASPL) website as targeting education with lottery revenue. Many states slice their lottery pie to support multiple entities.

Not so in Georgia, with every dollar going to education (including pre-K) aside from operating expenses and winning ticket-holders. According to La Fleur’s Lottery World, Georgia ranks second in highest per capita returns to beneficiaries for states without video lottery terminal revenue.

The nation’s appetite for lottery participation has not abated. Total contributions to beneficiaries last year exceeded $30 million, according to the NASPL, with the amount increasing annually in recent years even as other types of gambling have cropped up.

In Georgia, which has not legalized alternate forms of wagering in large part to protect the lottery and the HOPE scholarship, about $1.5 billion has been returned to education in each of the past three years, about 20% above 2019 and ’20.

‘Not very stable revenue sources’

Lottery sales are subject to external factors such as recessions. In 2011, reduced revenue forced the legislature to scale back, with tuitions no longer fully covered. As the economy rebounded, it restored the full tuition amount last year.

“Lotteries are generally not very stable revenue sources,” said Ross Rubenstein, a Georgia State professor who has studied different kinds of financial aid for college students. “Most states, including Georgia, have had to increase payout rates over time to try and keep interest and sales up.”

Riley, noting the return of full coverage, said, “We’re feeling confident at this point that this is sustainable.”

Nonetheless, Gov. Brian Kemp has pledged to provide full state funding in the event the lottery falls shy. And he recently vetoed a proposal that would have permitted students to take graduate-level courses on the HOPE because it could have stretched the resources too thin.

The great lottery debate

Georgia’s funding format is not universally applauded.

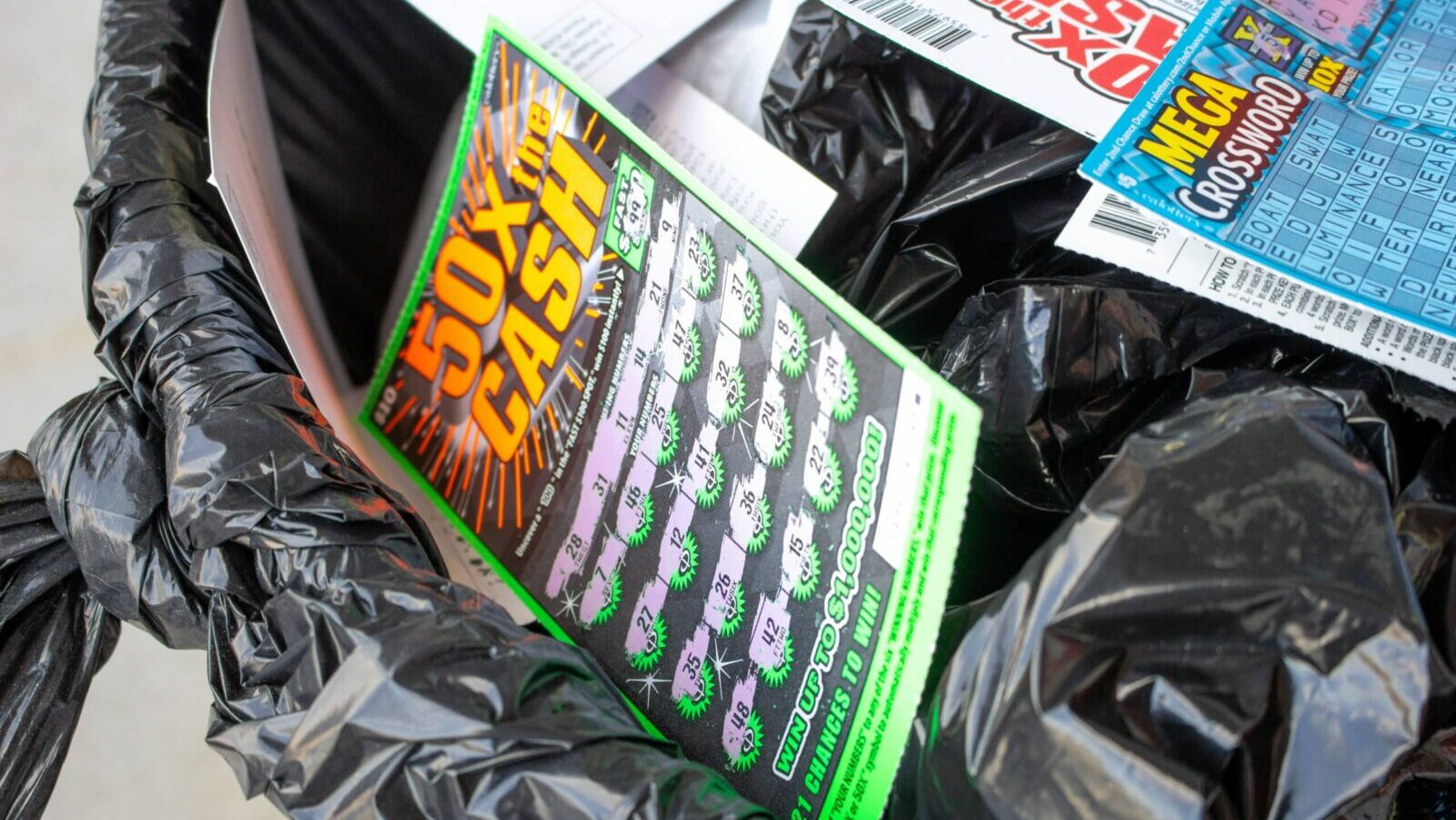

For one, some critics regard the lottery as a regressive tax, given that its participants are disproportionately lower-income.

Riley maintains that the system is preferable to funding scholarships through taxes.

“A tax is something that’s involuntary,” she said. “I see participation in the lottery as voluntary.”

Georgia’s merit-based component favors families less likely to require relief than those from lower-income brackets, some say.

Rubenstein co-authored research that found 46% of students without merit scholarships in the university system hail from families with income below $30,000, compared to 17% with income above $100,000.

“So the lottery and HOPE together are an income transfer from lower-income to middle- and upper-income households,” he said.

The minimum GPA stipulation, while an incentive to stay focused academically, also unduly impacts lower-income students, Rubenstein concluded.

“They’re also significantly more likely to lose the scholarship in college … so the initial inequalities in scholarship receipt actually widen over the course of students’ college careers.”

Level playing field?

Rubenstein credits the Georgia lottery for positive outcomes on education. Asked whether the setup is fair, he said, “It’s a matter of opinion, though I suspect many people would think it’s not.”

Among those who find fault with Georgia choosing the HOPE recipients based exclusively on merit is Jordan Madden.

“The downside is it does leave a lot of people at a disadvantage — more Black and Brown students,” said the senior-to-be, who aspires to become an education policy advocate. “Whiter kids and whiter schools have better access to education because of the HOPE.”

Symone Hill, like Madden a rising senior at Georgia State, learned about the scholarship as a high school freshman. Because the family likely could not have initially afforded an upper-tier four-year school for Hill and her twin sister, she remembers her mother saying, “Make sure you keep that 3.0 [GPA].”

“That wasn’t hard for me,” recalled the interdisciplinary studies major and possible future lawyer. “School is, like, my thing.”

With lottery revenue funneled directly to scholarships, Hill said she never considered an out-of-state college.

Asked if she were grateful for the HOPE, she said, “100 percent. Definitely.”