From Millions To Billions: Economist Matheson On The Lottery’s Rise And Its Future

"Jackpot fatigue" is a very real phenomenon, as Matheson explains: "Nowadays, no one bats an eye at a hundred million."

6 min

Over the course of his recent interview with Lottery Geeks, economist and lottery expert Dr. Victor A. Matheson shared a mountain of fascinating information and insight about the lottery — so much so, in fact, that it made sense to split the interview into two parts.

In Part One, Matheson discussed his long history with studying the lottery and tackled such topics as how the revenue is divided and which numbers are best to play. Here in Part Two, we’ll uncover how the lottery industry has changed in recent decades and explore where it’s headed.

With iLottery entering the equation and sports betting emerging as a possible form of competition for the gambling dollar, the answers regarding the future of the lottery are complex — and fascinating.

Lottery Geeks (LG): You’ve been following the lottery for a while. What are the biggest changes you’ve noticed in lottery offerings over the past two decades?

Victor Matheson (VM): The biggest thing has been the rise of the gigantic multi-state lotteries. The first multi-state lottery was actually in 1985. The little tiny states of New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine all joined together to offer the tri-state lottery. And because of the ability to join together, they were able to offer a lottery with longer odds, so a lower chance of winning, which means that those jackpots would roll over more times, which means you’d get these higher jackpot numbers. But there were enough players that the jackpot would rise fairly quickly, and people would win commonly enough that people didn’t think that it was just impossible to win.

So that was the first [multi-state] lottery, and soon after that, Lotto America came about with a bunch of, again, small states that couldn’t offer big jackpots on their own. The Kansases and the Vermonts and the Idahos could all come together for this. And Lotto America eventually morphed into Powerball. And then you also have this rival organization: The Big Game, which became Mega Millions, formed. And then about ten years ago, these two rival organizations basically called a truce, and we went from having these kind of big regional multi-state lotteries to two giant multi-state lotteries that basically go across the entire country. So every state with a lottery basically offers both of these lotteries, and that’s how we get lotteries that have billion-dollar-reported advertised jackpots.

You know, back when I first started, a hundred-million-dollar advertised jackpot was something that was unheard of, and now we’ve had almost a dozen billion-dollar jackpots advertised.

LG: How have these bigger jackpots impacted the mindset of an average player?

VM: Well, it certainly is the case that you don’t get “Lotto fever” where people are lining up out the door for a hundred-million-dollar jackpot. We barely see any response when a jackpot goes over a hundred million. [Previously,] these were front-page news. These were five o’clock news stories on the local TV when the California or the Florida or the New York or Pennsylvania lottery hit a hundred million dollars back in those days 20 years ago. Nowadays, no one bats an eye at a hundred million. We don’t even start seeing any sort of significant news media until we’re getting close to a billion or above. And, soon it’s going to be that even a billion dollars is old hat and we only care about two billion dollars.

There’s a phenomenon that researchers call “lotto fatigue” or “jackpot fatigue” that, you know, we get tired of a mere hundred million dollars. It takes a billion dollars now. [First] we get tired of a mere five million dollars. We’re talking about 50. Then we’re talking about 500 million. Then we’re talking about a billion. And there’s probably no end to that.

LG: How has increasing income inequality in the U.S. impacted lottery participation?

VM: That’s a pretty good question. So, we do know that lottery tickets overall are a highly regressive form of taxation. So what we mean by that is it’s a tax where the poor pay a higher percentage of their income than the rich.

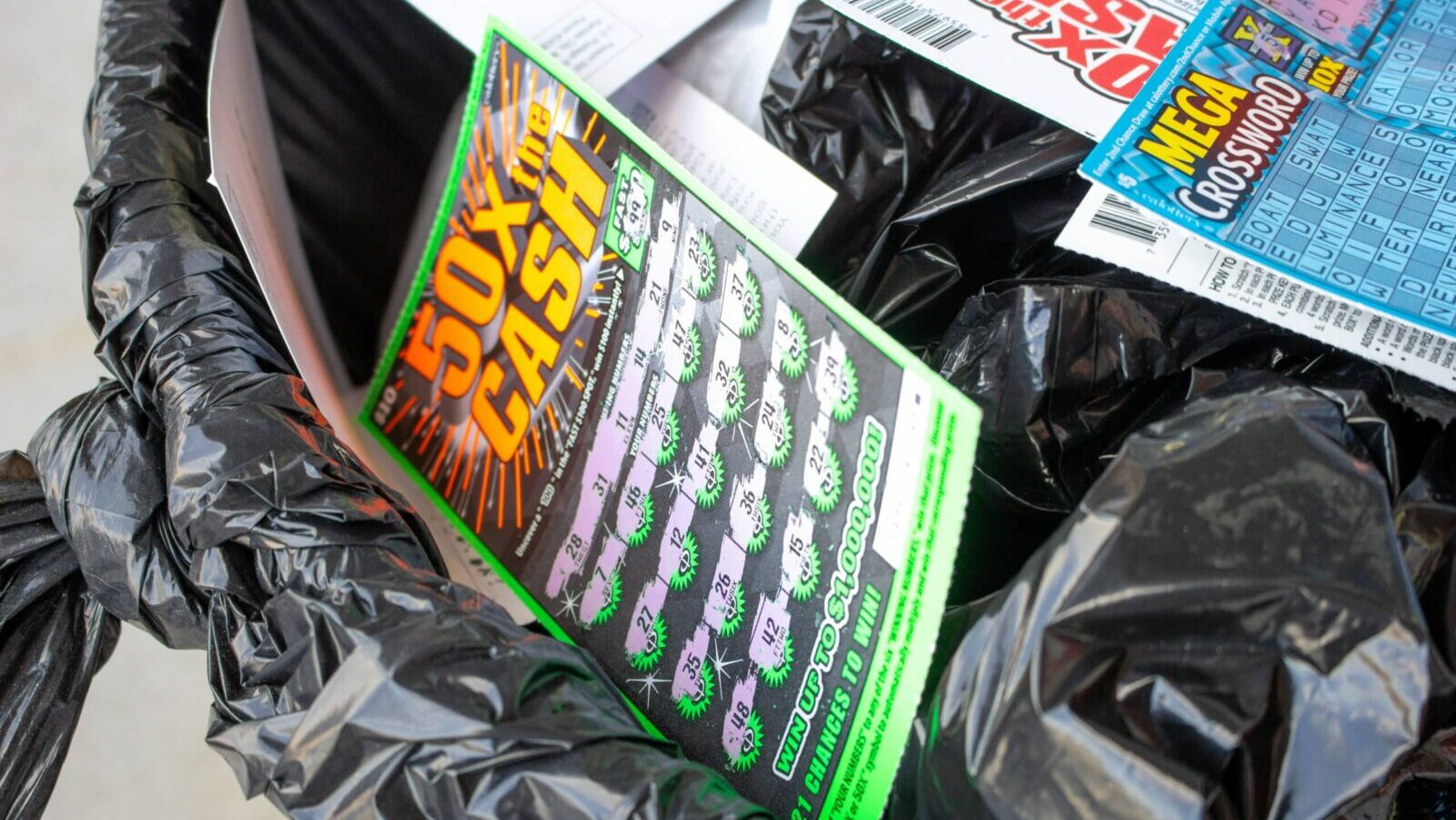

But not every game is the same. Scratch-off tickets — the instant win tickets, you buy them at any convenience store — those are purchased fairly uniformly across all income levels. But that doesn’t mean it’s not regressive. In fact, that means it’s highly regressive because if people across every income distribution are purchasing roughly the same number of tickets, that means that as a percentage of their income, the poorest fifth of the population is purchasing a lot more scratch-off lottery tickets than a person in the richest fifth of the population.

However, when it comes to Powerball — especially when you get up to the billion-dollar sort of numbers — those numbers are actually much less regressive. You really see lots more high-income people entering into the lottery market … to the point where at the highest jackpots, Powerball and Mega Millions don’t appear to be particularly regressive anymore, which is kind of nice. Because even for a Mitt Romney or a Donald Trump, a billion-dollar jackpot is a big prize.

LG: Since we’re speaking about how the lottery industry is changing, how would you say that the digitization of the lottery, like iLottery, for example, may affect the future of the industry?

VM: This is a huge issue. And this is an issue that’s almost certainly being pushed very, very rapidly into an online direction by sports betting.

When it comes to the actual return on your investment, of course, you should never think of gambling as an investment. But when it comes to thinking about gambling, about what you get back when you buy a ticket, the lottery has one of the very worst returns of any gamble out there. For scratch tickets, the house or the lottery association takes about 25 percent of the ticket price out. When it comes to Powerball, they take about 40 percent of the money out. So this is a huge house edge.

But sports betting is only about 8 percent. Blackjack, if you’re playing well and you’re following the best possible strategy, only takes out about 1 percent. And so the lottery is a terrible gamble compared to everything else.

But what it has going for it is that it’s convenient, right? Massachusetts has something like 7,500 lottery retailers. So that means that it’s easy to go buy a lottery ticket. But we only have three casinos [here.] So if you want to play blackjack, you have to drive a ways and it’s hard to do. But if I want to gamble with just a quick Powerball ticket or a quick instant game, I can do that by just driving down the block.

Still, the advent of sports gambling has meant that it’s become much easier to gamble in other ways — ways that are even more simple than driving to the local 7-Eleven. I have an app on my phone where I can make a bet on tonight’s NBA games or tonight’s University of Iowa women’s basketball game with Caitlin Clark. I can make those sorts of bets from my phone. And so that convenience factor that the lottery used to have is kind of gone.

And so the question is: Where does the lottery go when there are other forms of gambling that are equally convenient? And I think one of the places it’s going is online, which means we basically put a casino in every single American’s pocket.

LG: And how will this affect sales in, let’s say, 10 years?

VM: Hard to know. Certainly Powerball and Mega Millions are likely to stay around for the foreseeable future because they offer those very high jackpots, and it’s extremely difficult to stimulate or replicate that in a casino game or in a sports bet. And those might actually grow as it becomes easy to buy lottery tickets on your phone.

Hard to know what happens to that instant win market, though, that allows you to win $10 instantly or $5 instantly, because those are the sort of things that you could buy with a sports bet pretty easily as well. It’s hard to know whether the lottery can compete against that substitute gambling product that is sports gambling.

LG: So with the lottery and sports betting being so accessible on phones, and with Generation Z and Generation Alpha spending the majority of their time on their phones, do you think these generations will actually be playing the lottery more or betting more than previous generations?

VM: Well, we know that every generation has gambled like crazy. Here in Massachusetts, the average adult buys over $1,000 of lottery tickets a year. We’ve also seen that since the introduction of mobile [sports betting] just a year ago, we’re also making about $1,000 of sports bets a year. So people seem to have an almost unquenchable desire to gamble.

Obviously, we’re making products that are wildly addictive. And they know how to hit people’s buttons. They know how to trigger those things in your brain that give you that little hit of excitement, that little hit of dopamine that makes us want to go back again and again.

But we know that people have wanted to gamble forever. I mean, we’ve had Roman emperors that were such gamblers that they bankrupted the entire Roman Empire. So gambling to excess is certainly not a new thing in any way.